In this post I describe yet another approach for producing a more natural rendering of stereo recordings via headphones. Previously I was exploring the idea of adding the features of speaker playback that we usually find missing on headphones: the room reverb, the natural cross-feed between signals of the speakers when they reach ears, the effect of head and torso reflection, etc (see old posts like this one). The results were sounding to me more pleasing and more spatially "correct" than any commercial spatializer products I have tried. However, when staying in front of my LXdesktop setup while wearing headphones, and switching back and forth between playback over the speakers and the headphones, the difference is still obvious, with the speaker sound being so much wider and having more depth, while the playback via headphones is always sounding too close to the head, both in forward and lateral dimensions.

The new approach that I have tried and describe in this post is based on a multi-microphone capture of the sound field that the speakers and the room create, representing it as 3rd order Ambisonics, and then using binaural renderers. This rendering has ended up sounding surprisingly realistic, finally allowing to create with headphones an illusion that I'm listening to my speakers. Another interesting point that I will discuss is that, in some sense, this rendering can sound even better than the speakers used for making it.

Why Ambisonics?

Let's start with a simple question—why using Ambisonics at all, when the end result is still a two channel binaural rendering. Why go through this intermediate representation if we could just make a binaural capture of the speakers using a dummy head in the first place? We probably need to disambiguate what is meant by the "capture" here. Binaural recordings are a great way for capturing an event and that we want to listen to later. When we are listening back at the same place where the recording was taken, it usually sounds very convincing, as if we are hearing a real event. The cheapest available solution for such a capture is in-ear microphones, and I had tried using the mics by The Sound Professionals for this purpose.

The "event" that is being captured does not necessarily need to be a real performance, it can as well be a playback of a song over the speakers. The benefit of using speakers is that we can capture their properties and use them to listen back not only to this particular song as played by these speakers, but to any arbitrary song played by them. For that what we need is a capture of impulse responses (IRs) and apply them to a stereo recording via convolution. In the simplest case, we just need 2 pairs of IRs: one pair for left speaker to the left and to the right ear, and another pair for the right speaker. These IRs are usually called "BRIRs": "Binaural Room Impulse Responses."

The problem is that making a good capture of BRIRs using a live person's head is very challenging. The main difficulty is that due to noisiness of the environment and relatively long reverberation times of real rooms, the sweep signal used for the capture has to last for about 30–60 seconds, and the head must stay completely still during this time, otherwise the information about high frequencies will become partially incorrect.

As a side note, the same binaural capturing process is used for acquiring HRTFs of real persons, however, such an acquisition is done in anechoic chambers, thus the sweeps can be quite short—under 1 second, and there is usually some kind of a fixture used for preventing the subject's head from moving.

As another side note, I know that with Smyth Realiser they can actually capture BRIRs in customers' rooms in a "high fidelity" way, but it must be their "know how" and it is not trivial to match with a DIY approach.

Now, what if in our room, instead of a real person we use a dummy head, like Neumann KU100? That assumes it's OK for you to buy one—due to their "legendary" status in the audio recording industry they are very pricey. If you have got one, it is of course much easier to make a stationary setup because the artificial head is not moving by itself, it is not even breathing, thus capture of a good quality BRIRs is certainly possible.

However, the recorded BRIRs can not be further manipulated. For example, it is not possible to add rotations for head tracking, as that would require capturing BRIRs for every possible turn of the head (similar to how it's done when capturing HRTFs). So, another approach which is more practical, is to capture the "sound field" because it can be further manipulated, and then finally rendered into any particular representation, including simulation of a dummy head recording. This is what Ambisonics is about.

The Capture and Rendering Process

I've got a chance to get my hands on the Zylia Ambisonics microphone (ZM-1E). It looks like a sphere with the diameter slightly less than of a human head, and has 19 microphone capsules spread over the surface (that's much more than just two ears!). The Zylia microphone has a number of applications, including capturing of small band performances, recording sound of spaces for VR, and of course producing these calming recordings of ocean waves, rain, and of birds chirping in woods.

However, instead of going with this mic into woods or to a seashore, I stayed indoors and used it to record the output of my LXdesktop speakers. This way I could make ambisonics recordings that can be rendered into binaural, and even have support for head tracking. The results of preliminary testing in which I was capturing the playback of speakers have turned out to be very good. My method was consisting of capturing raw input from the ZM-1E—this produces a 19-channel recording, and this is what is called the "A-format" in the Ambisonics terminology. Then I could experiment with this recording by feeding it to the Ambisonics converter provided for free by Zylia. The converter plugin outputs 16 channels of 3rd order Ambisonics (TOA) which then can be used with one of the numerous Ambisonics processing and rendering plugins. The simplified chain I have initially settled upon is as follows:

A practical foundation for the binaural rendering of Ambisonics used by the IEM BinauralDecoder from the "IEM Plug-in Suite" is the result of the research work by B. Bernschütz which is described in the paper "A Spherical Far Field HRIR/HRTF Compilation of the Neumann KU 100". They have recorded IRs for the KU100 head which was rotated by a robot arm before a speaker in an anechoic chamber. Below is a photo by P. Stade from the project page:

This allowed producing IRs for the number of positions on a sphere that are enough for producing a realistically sounding high order Ambisonics rendering. The work also provides compensating filters for a number of headphones (more on that later), and among them, I have found AKG K240DF (the diffuse field compensated version) and decided to use it during preliminary testing.

Since the binaural rendering is done using a non-personalized HRTF, in order to help the auditory system to adapt, it's better to use head tracking. Thankfully, with Ambisonics the head tracking can be applied quite easily with a plugin which is usually called "Rotator". The IEM suite has one which is called SceneRotator. It needs to connect to the head tracking provider which is usually a standalone app via the protocol called OSC. I have found a free app called Nxosc which can use the Bluetooth WavesNX head tracker that I had bought a long time ago.

Somewhat non-trivial steps for using IEM SceneRotator with Nxosc are:

- Assuming that Nxosc is already running and has been connected to the tracker, we need to connect SceneRotator to it. For that, click on the "OSC" text at the left bottom corner of the plugin window. This opens a pop-up dialog and in it, we need to enter 8000 into the Listen to port field, and then press the Connect button.

- Since our setup is listener-centric, we need to "flip" the application of Yaw, Pitch, and Roll parameters by checking "Flip" boxes under the corresponding knobs.

As a result, the SceneRotator window should look like below, and the position controls should be moving according to the movements of the head tracker:

And once I made everything working... The reproduced renderings sounded astonishingly real! In the beginning, there were lots of moments when I was asking myself—"Am I actually listening to headphones? Or did I forget to mute the speakers?" This approach to rendering has turned out to be way more realistic than all my previous attempts, finally I have got the depth and the width of the sound field that matched the speaker experience—great!

A-format IRs

And now the most interesting part. After I had played enough with ambisonic captures of speaker playback, I decided that I want to be able to render any stereo recording like that. Sure, there are enough plugins now that can convert stereo signals into ambisonics and synthesize room reverb: besides the plugins from the IEM suite, there is SPARTA suite (also free), and products by dearVR. However, what they synthesize is some idealized speakers and perfect artificial rooms, but I wanted my real room, and my speakers—how do I do that?

I realized that essentially I had to get from two stereo channels to Ambisonics. Initially I was considering capturing IRs of the output from the Zylia's Ambisonics plugin for my speakers. However, I was not sure whether the processing that the plugin performs is purely linear. Although the book on Ambisonics by F. Zotter, M. Frank describes the theory of the transformation of A-format into B-format as a matrix multiplication and convolution (see Section 6.11), I was still not sure whether in practice Zylia does just that, or it also performs some non-linear operations like decorrelation in order to achieve a better sounding result.

Thus, I decided to go one level of processing up, and similar to BRIRs, capture the transfer function for each pair of my speakers and the microphone capsules of the Zylia mic. This is for sure an almost linear function, and it is fully under my control. However, that's a lot of IRs: 2 speakers by 19 microphones makes it 38 IRs in total! And in order to be correctly decoded by Zylia's plugin these IRs have to be relatively aligned both in time and in level, so that they represent correctly the sound waves that reach the spherical microphone and get scattered over its surface.

Thankfully, tools like Acourate and REW can help. I have purchased the multi-mic capture license for REW. This way, I could capture inputs to all 19 microphones from one speaker at once, and what's important, REW maintains the relative level between the captured IRs. However, maintaining time coherence is more tricky. The problem is that REW sets the "start" of the IR at the sample with the maximum value which usually corresponds to the direct sound of the speaker. However, for IRs captured by the mics on the rear part of the sphere, the power of the reflected sound from room walls can actually be higher than the power of the direct sound, thus the "start" position of the IR chosen by REW is not always correct. That's one problem.

Another problem is aligning the levels between the captures of the left and the right speaker. Since they are captured independently, and REW normalizes the captured IRs, the resulting levels between the left and the right speakers may be mismatched.

In order to solve both of these alignment problems, I have captured with the same Zylia setup periodic pulses played in turn by the left and the right speakers. Then by convolving the produced IRs with the original test signal, and comparing the result with the actual recorded signal, I could see whether the timing and level of IRs is correct.

I have performed this alignment manually, which of course was time-consuming. I think, if I ever want to do this again, I would try to automate this process. However, it was actually interesting to look at the waveforms because I could clearly see the difference between the waveforms that were actually captured in the room, and the ones obtained by a convolution with the captured IRs. They actually look very different, see an example below:

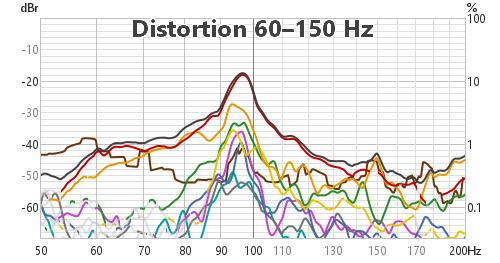

What we can see is that the pulse rendered via convolution (red trace) has much lower noise, and looks more regular than an actual capture (green trace). This is because the IR only captures the linear part of the acoustic transfer function. There is actually a whole story on how captures done with the logarithmic sweep relate to the parameters of the original system, I will leave it for future posts. In short, by rendering via the captured IR, we get rid of a lot of noise, and leave out any distortions. So in some sense, the produced sound is a better version of the original system which was used for creating the IRs.

After producing these IRs, I enhanced the rendering chain in order to be able to take a stereo input, and produce 20 (19 mic channels plus 1 silent) channels of audio which emulate the output from the Zylia's microphone, that is the A-format, which is then fed into the Zylia's ambisonics decoder (note that on the diagram we only count channels that actually have signal):

It was an unusual experience for me to create a 40-channel track in Reaper, that's in order to duplicate the left and the right stereo signals into 20 channels for applying the A-format IRs. However, it worked just fine. I truly appreciate robustness and reliability of Reaper!

One issue remained though. Since Zylia is not a calibrated measurement microphone, it imprints its own "sound signature" on the captured IRs. Even by looking at transfer functions of these IRs I could see that both bass and high frequencies have some slope which I did not observe while performing the tuning of LXdesktop. Thus, some correction was needed—how to do it properly?

Zylia Capture and Headphones Compensation

Yet another interesting result of the "Spherical Far Field HRIR/HRTF Compilation" paper is that if we take all frequency responses for all these positions captured by the KU100 head around the sphere, and average them, the result will deviate from the expected diffuse field frequency response by a certain amount, as we can see on the graph below, adapted from the paper, which is overlaid with the graph from the KU100 manual showing the response (RTA bars) of the KU100 in a diffuse field:

I used the actual diffuse field frequency response as the target for my correction. The test signal used in this case is uncorrelated stereo noise (zero interchannel correlation, see notes on ICCC in this post). Note that the "Headphone Equalization" in IEM BinauralDecoder has to be turned off during this tuning.

And this adjustment works, however applying it also "resets" the speaker target curve, so I had to re-insert it into the processing chain. With that, the final version of the processing chain looks like this:

Now if we turn back on the headphone equalization in the IEM BinauralDecoder, it will compensate both for the deviations from the diffuse field for the KU100 head and the selected headphones.

It's funny that although AKG K240DF is described by AKG as a diffuse field compensated headphone, in reality, however deviations as much as 3 dB from the diffuse field response across frequency bands is a norm. Usually the deviations exist on purpose, to help make listening to "normal" non-binaural stereo recordings more pleasant and in addition to produce what is known as the "signature sound" of the headphone maker.

Would Personalized HRTF Work Better?

I was actually surprised by the fact that use of non-personalized HRTFs (even non-human, since they were captured on a KU100 artificial head) works that well for giving the outside-of-head sound experience, and sufficiently accurate localization, including above and behind the head locations. I was wondering what an improvement would be if I actually had my own HRTF captured (I haven't yet, unfortunately) and could use it for rendering?

One thing I have noticed with the non-personalized HRTF is that tonal color may be inaccurate. A simple experiment to demonstrate this is to play mono pink noise and then pan it, with simple amplitude panning, to left and right positions. On my speakers, the noise retains its "color", but in my binaural simulation I can hear difference between the leftmost and the rightmost positions. Since I'm not a professional sound engineer, it's hard for me to equalize for this discrepancy precisely "by ear", and obviously, no measurement would help because this is how my auditory system compensates for my own HRTFs.

By the way, while seeking information for some details related to my project I have found a similar research effort called "Binaural Modeling for High-Fidelity Spatial Audio" done by Viktor Gunnarsson from Dirac which helped him to obtain a PhD degree recently. The work describes a lot of things that I was also thinking of, including the use of personalized HRTFs.

The fun part is that Viktor also used the same Zylia microphone, however unlike me, he also had access to a proper Dolby Atmos multichannel room, you can check out his pictures in this blog post. I hope that this research will end up being used in some product intended for end users, so that audiophiles can enjoy it :)

Music

Finally, this is a brief list of music that I had sort of "rediscovered" while testing my new spatializer.

"You Want it Darker" by Leonard Cohen which was released in 2016 shortly before his death. I'm not a big fan of Cohen, but this particular album is something that I truly like. The opening song creates a wide field for the choral, and Cohen's low voice drops into its net like a massive stone. It makes a big difference when in headphones I can perceive his voice as being at a hand distance before me, as if he is speaking to me, instead of hearing it right up to my face, which feels a bit disturbing. This track helps to evaluate whether the bass is not tuned up too much, as otherwise the vibration of headphones on your head can totally ruin the feeling of distance.

"Imaginary Being" by M-Seven, released in 2011. It was long before the Dolby Atmos was created, but still sound of this album delivers a great envelopment, and it feels nice being surrounded by its synthetic field. My two favorite tracks are "Gone" and "Ghetto Blaster Cowboy" which creates an illusion of being in some "western" movie.

"Mixing Colours" by Roger and Brian Eno, released in 2020 is another example of enveloping sound. Each track carries a name of a stone, and they create a unique timbre for each one of them. Also, Brian Eno is a master of reverb which he uses skillfully on all of his "ambient" albums, including this one, giving a very cozy feeling to the listener.

The self-titled album by Penguin Café Orchestra, released in 1996. I have discovered this band by looking at the list of releases done by the Brian Eno's experimental "Obscure Records" label. The music is rather "eccentric" and sometimes experimental—check the "Telephone and Rubber Band" track for example. However, overall it's a nice work, with lots of different instruments used, which are placed in the sound field around the listener.

"And Justice for All" by Metallica, released in 1988—not an obvious choice after the selection of albums above—this one was suggested by my son. After I have completed setting up my processing chain and wanted to have an independent confirmation that it really sounds like speakers, I have summoned my son and asked him to listen to any track from Apple Music. And he chose "Blackened". In the end, it has turned out to be a good test track for number reasons: first, since it's the "wall of sound" type of music, with lots of harmonic distortion, it's a great way to check whether the DSP processing chain is clean, or does it add any unpleasant effects ("digitis" as Bob Katz calls it) that would become immediately obvious. Second, again it's a good test to see if the amount of bass is right in the headphones. As one usually wants to listen to metal at "spirited" volume levels, any extra amplification of bass frequencies will start shaking the headphones, ruining the externalization perception. And the final reason is that listening in the "virtual studio" conditions that binauralized headphone sound creates allows to hear every detail of the song, so I got a feeling that during more quiet passages of "Blackened"—for example the one starting after the time position 2:50—I can hear traces of the sound of Jason Newsted's bass guitar which was infamously brought down during mixing of this album. Later I have confirmed that it's indeed the bass guitar by listening to a remix done by Eric Hill on YouTube which had brought its track back to a normal level.

Conclusions and Future Work

This experiment of creating a binaural rendering of my desktop speakers using an ambisonics microphone has demonstrated a good potential for achieving high fidelity realistic headphone playback at relatively low cost. In future this is what I would like to explore and talk about:

- use of other models of headphones, especially those that are missing from the dataset captured by B. Bernschütz and thus do not present in the headphone equalization list of the IEM BinauralRenderer plugin;

- additional elements of processing that improve the sound rendered via this chain;

- use of other head trackers, like HeadTracker 1 by Supperware;

- individualization of the headphone transfer function and binaural rendering;

- ways to compare the headphone playback to speaker playback directly.

Also, one thing I would like to experiment on is doing processing of the left and the right speaker signals separately. Currently we mix the signals from the speakers at the input of the simulated Zylia microphone. However, since the microphone is significantly smaller and is less absorptive compared to a human head and torso, it does not achieve the same level of cross talk attenuation that I have on my physical speakers. So the idea is that we should try processing the input from the left and the right speakers separately, in parallel. And only after we get to the Ambisonics version of the signal, or maybe even to the binaural rendering, we mix these signals together, providing necessary cross-talk cancellation. I'm not sure how to do that in the Ambosonics representation, but in the binaural version it's pretty easy because we will end up having simulated BRIRs, that is, two pairs of two channel signals, so we can attenuate the contra-later signal as desired. In some sense, this approach simulates a barrier installed between the ears of the listener, but without the need to deal with side effects of an actual physical barrier.